In the book by Tito Colliander, The Way of the Ascetics, a brief conversation is recorded between a monk and a layman. The layman asks the monk, “What do you do there in the monastery?” And the monk replies, “We fall and get up, fall and get up, fall and get up again.” It’s not …

In the book by Tito Colliander, The Way of the Ascetics, a brief conversation is recorded between a monk and a layman. The layman asks the monk, “What do you do there in the monastery?” And the monk replies, “We fall and get up, fall and get up, fall and get up again.” It’s not only in monasteries that we do that. In a fallen and sinful world, an all important aspect of our personhood is our need to be healed, to get up after we’ve fallen, our need to repent, to forgive, and to be forgiven.

Are any among you sick? They should call for the presbyters of the church and have them pray over them, anointing them with oil in the name of the Lord. And the prayer offered in faith will save the sick, and the Lord will raise them up. If anyone has committed sins, they will be forgiven him. Therefore, confess your sins one to another and pray for one another so that you may be healed (James 5:16).

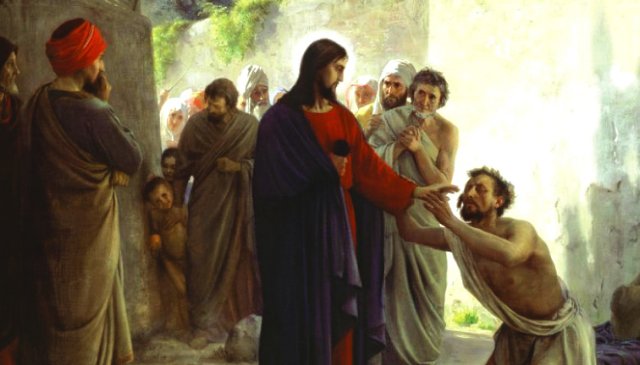

What we notice in this passage is that St. James is speaking about healing in an allembracing sense of body and soul together. He talks about the sick person being healed through anointing with oil, but he also says that the sick person will be forgiven his sins. So, healing of body and soul go together. We are to see the human person, as we already said, in holistic terms. An undivided unity: the body is not healed apart from the soul, nor the soul apart from the body. The two are interdependent. St. James speaks at one and the same time of the sick person being raised from his bed physically healed, and he speaks of the forgiveness of his sins through confession. He speaks of spiritual healing.

I find this to be a key that opens a very important door, a vital clue — the anointing of the sick and confession are essentially connected as two indivisible aspects of a single mystery of healing and forgiveness. Each has its own specific function — they do not replace one another, but together they form a true union. So, perhaps the most helpful way to look at the sacrament of confession is to see it as a sacrament of healing.

Now, sacramental confession as we know it today in the Orthodox Church represents a convergence of two things which originally were, perhaps, distinct. First of all, there is the administration of penance. This is particularly connected with John, chapter 20, verses 22 through 23. There, the risen Christ breathes on His disciples, confers on them the gift of the Holy Spirit, and, He says, “whosoever sins you forgive, they are forgiven; whosoever sins you retain, they are retained.”

There, the risen Christ gives to His disciples the power of binding and loosing sins — a juridical power. This task of binding and loosing was transmitted from the apostles to their successors, the bishops. In the early church, the administration of penance was something public; it didn’t involve the private giving of counsel or advice. It was something exceptional. You hoped, by God’s mercy, that you wouldn’t have to be involved in penance. Indeed, the penances that were imposed were by our standards extremely severe.

Then there is another source of the sacrament of confession as we know it today. This is the practice of spiritual counsel, first found especially in the Egyptian monasticism of the fourth century, though no doubt the practice of using spiritual counsel goes right back to apostolic times. But we don’t know very much about it until the emergence of monasticism.

In the desert of Egypt, as we have learned from the Sayings of the Desert Fathers an important part was played by the disclosure of thoughts. The disciple would go perhaps daily to his spiritual elder, and open his heart to him. Now this is something clearly different from the system of public penance. First of all, it is regular, not exceptional. In many monastic centers, this happens daily. Secondly, it is private, not public. It’s carried out under conditions of confidentiality. It doesn’t directly involve the church hierarchy.

The spiritual father — in a monastic context, the elder — may in fact be a layman, not a priest. Anthony of Egypt was never a priest but he formed in many ways the prototype of the monastic spiritual father. Athanasius calls him “a physician given by God to all of Egypt”.

In this practice of spiritual counsel, the scope is far wider than in the formal penance of the Church. What you disclose to your elder is not just your sins, but your thoughts. You don’t just speak of what you’ve done wrong, you share with him your inner state, your whole situation. The hope is that by revealing your thoughts to your elder, you will in fact avoid falling into sin. In other words, penance is retrospective, picking up the pieces after the breakage; but, through the use of spiritual counsel, you hope to avoid the breakage itself.

The underlying principle behind this monastic disclosure of thoughts is very clear; it is described in this way in the Sayings of the Desert Fathers: If impure thoughts trouble you, do not hide them, but tell them at once to your spiritual father and condemn them. The more a person conceals his thoughts, the more they multiply and gain strength. But an evil thought, when revealed, is immediately destroyed. If you hide things, they have great power over you, but if you could only speak of them before God, in the presence of another, then they will often wither away, and lose their power.

The process of bringing into the open what is hidden is decisive behind spiritual counsel. That, of course, is also the principle in modern psychotherapy, but the desert fathers thought of it before Freud and Jung.

Now, in our view of confession today, where do we put the primary emphasis? Do we put it mainly on the aspect of penance, or on the aspect of spiritual counsel? Do we think of confession primarily in juridical terms, as coming to Christ as the Judge? Do we think of it, on the other hand, more in therapeutic terms, as coming to Christ as the Good Physician, the Doctor? Do we see sin primarily as the breaking of the Law, in medieval terms, or do we see sin more as the symptom of inner illness?

We shouldn’t feel we’ve got to think of confession either in legalistic terms or in terms of healing, but we should combine the two. Even so I have to say that I myself find the therapeutic model much more helpful — to see confession above all as a sacrament of healing, to think of it as coming to Christ the Doctor. The priest is not the doctor, he is the medical assistant. If you’re given a penance — that’s not a punishment, it’s a tonic to help you recover afterwards, to get better.

Join Us: Sign Up Today!

Tags: