By: Rodney Stark At the height of the second great epidemic, around 260, in his Easter letter, Dionysius Patriarch of Alexandria wrote a lengthy tribute to the heroic nursing efforts of local Christians, many of whom lost their lives while caring for others. Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing …

By: Rodney Stark

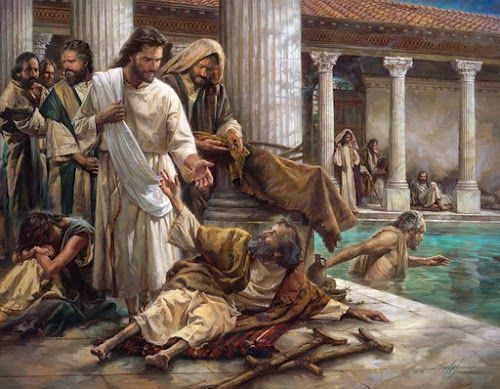

At the height of the second great epidemic, around 260, in his Easter letter, Dionysius Patriarch of Alexandria wrote a lengthy tribute to the heroic nursing efforts of local Christians, many of whom lost their lives while caring for others.

Most of our brother Christians showed unbounded love and loyalty, never sparing themselves and thinking only of one another. Heedless of danger, they took charge of the sick, attending to their every need and ministering to them in Christ, and with them departed this life serenely happy; for they were infected by others with the disease, drawing on themselves the sickness of their neighbors and cheerfully accepting their pains. Many, in nursing and curing others, transferred their death to themselves and died in their stead. . . . The best of our brothers lost their lives in this manner, a number of presbyters, deacons, and laymen winning high commendation that death in this form, the result of great pie and strong faith, seems in every way the equal of martyrdom.

Dionysius emphasized the heavy mortality of the epidemic by asserting how much happier survivors would be had they merely, like the Egyptians in the time of Moses, lost the firstborn from each house. For “there is not a house in which there is not one dead – how I wish it had been only one.” But while the epidemic had not passed over the Christians, he suggests that pagans fared much worse: “I full impact fell on the heathen.”

Dionysius also offered an explanation of this mortality differential. Having noted at length how the Christian community nursed the sick and dying and even spared nothing in preparing the dead far proper burial, he wrote:

The heathen behaved in the very opposite way. At the first onset of the disease, they pushed the sufferers away and fled from their dearest, throwing them into the roads before they were dead and treated unburied corpses as dirt, hoping thereby to avert the spread and contagion of the fatal disease; but do what they might, they found it di cult to escape.

But should we believe him? If we are to assess Dionysius’s claims, it must be demonstrated that the Christians actually did minister to the sick while the pagans mostly did not. lt also must be shown that these different patterns of responses would result in substantial differences in mortality.

It seems highly unlikely that a bishop would write a pastoral letter full of false claims about things that his parishioners would know from direct observation. So if he claims that many leading members of the diocese have perished while nursing the sick, it is reasonable to believe that this happened. Moreover, there is compelling evidence from pagan sources that this was characteristic Christian behavior. Thus, a century later, the emperor Julian launched a campaign to institute pagan charities in an effort to match the Christians. Julian complained in a letter to the high priest of Galatia in 362 that the pagans needed to equal the virtues of Christians, for recent Christian growth was caused by their “moral character, even if pretended,” and by their “benevolence toward strangers and care for the graves of the dead.” In a letter to another priest, Julian wrote, “I think that when the poor happened to be neglected and overlooked by the priests, the impious Galileans (Christians) observed this and devoted themselves to benevolence.” And he also wrote, “The impious Galileans support not only their poor, but ours as well, everyone can see that our people lack aid from us”

(From: Rodney Stark, the Rise if Christianity)