Our need for Christ The greatest experience which strongly drew my attention during my early Christian life is that whenever I felt my want of so many things in my dealings with the people, the Church or the monks, I got so distressed and agonised that my energy, ministry and influence upon others were consequently …

Our need for Christ

The greatest experience which strongly drew my attention during my early Christian life is that whenever I felt my want of so many things in my dealings with the people, the Church or the monks, I got so distressed and agonised that my energy, ministry and influence upon others were consequently emasculated. But the moment I approach the person of my Lord Jesus and become aware of Him as though He were coming back after an absence of which I was always the cause, my heart leaps with joy and my mind gathers up so that all sense of want falls away from me and Christ rises over the horizon of my whole life. Then I see Him more than all my needs and feel His fullness overflowing and sweeping my life in the tide of His love which transcends the mind.

In the same measure I had this sense whenever I was so troubled with storming thoughts about the ways of God and His care for individuals and people that my spirit was sorely distressed within me. For I was always eager to see God supreme at all levels, of mercy or of justice and chastening, of tender fatherhood or sovereignty and grace, and remained thus torn asunder with conflicting feelings which gave me no rest or peace. But once I feel Him approaching me my soul calms down immediately, all my questions and worries vanish from me, and Christ appears transcending all our mental criteria concerning mercy or justice, fatherhood or sovereignty. At such moments Christ reveals to us the mystery of His will.

Through these two experiences I have been assured that Christ is the sole need of our life, and that the more distant we are from Him the greater our needs for so many things of this world, and the more our worrying regarding things particular or general in our life.

Why then is it that the person of Christ appears in this way as though He were the fullness of everything, and the sole answer which copes with a thousand questions, or rather does away with

every question?

To answer this we must realise that human nature comprises two contradictory worlds, the physical and the spiritual. This spiritual world which runs through man’s being contrasts with a materialistic and degenerate reality in the life of man which leads him to commit acts of utter baseness. A man may kill his brother for a morsel of bread or sell his heavenly heritage for a meal of pottage (Gen 27). The history of civilisation, philosophy and science proves that there is no hope of establishing a natural reconciliation in the tension and disruption inherent in man’s being between the ideals of the spirit and the realities of the flesh–whether through the interference of wisdom, the refinement of skills or the mere following of the commandments of God, or even caning. For as soon as human instincts rage, man rebels against all spiritual values, and a temporary spiritual blindness overpowers him and drives him to commit the grossest transgressions even against himself.

Here appears Christ in his full humanity and full divinity as the great miracle which reconciled the human reality-apparent in man’s instincts and passions in his dealings with the world, and his needs and infirmities–with spiritual ideals, or rather with God Himself. The conciliation is complete, perpetual and eternal, deeply rooted in the depth of man himself, for all that belongs to Christ has come to belong to mankind.

Here Christ has become at once man’s miracle and God’s miracle-man’s miracle because he has reached the depth of God’s nature, and God’s miracle because He has penetrated to the depth of man’s nature. In order to enter into the light of this miracle we have to realise that this conciliation does not rest on a theory however elaborate, nor on the mere following of commandments. The conciliation fulfilled by Christ is a personal conciliation achieved in Christ Himself, not through our power but through His power, and the result surpasses the mind of man. Enough to realise that the moment it was fulfilled through the Incarnation and Crucifixion of Christ, it comprised all humanity in the person of Jesus who represents it before God the Father.

Man is reconciled to himself, for God was reconciled in the body of our humanity which belongs to Christ and which He took from us. Hence we say confidently and succinctly that we are reconciled with God in Christ. It is a highly personal reconciliation, a sort of unique mediation undertaken by this sole mediator, Christ, between God and man, giving rise to a new force which entered earth or rather heaven.

The lesser and weaker image of our Christianity is our vain attempts to apply the commandments of Christ to our daily problems without Christ Himself, while the stronger and greater image obtains when “the person of Christ” enters our life. Then all our problems fall at once and we rise to the level of Christ’s commandments without the least personal skill.

The bitterness experienced by the Christian within himself as a result of the daily disruption whenever he comes up against Christ’s commandments and finds himself incapable of catching up with them although he loves them, is the outcome of his attempt to fulfil the commandments of Christ without Christ, which is impossible. Christ laid down the commandment that we may prove by it His presence: “Prove your own selves, know ye not your own selves, how that Jesus Christ is in you, except ye be reprobates?” (2Cor 13:5).

Hence the Lord says: “He who loves my keeps my commandments” (Jn 14:21) in the sense that he who loves me is he who can follow my commandments. First Christ’s person, then follows all that is Christ’s.

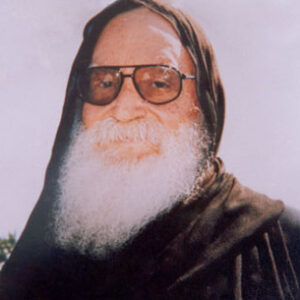

By: Fr Matta El-Maskeen (Matthew the poor)

Join Us: Sign Up Today!

Tags: