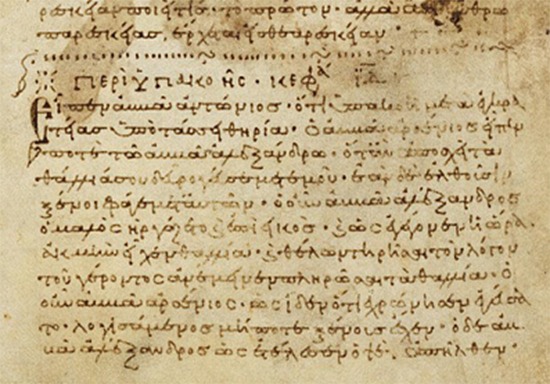

The Apophthegmata Patrum is an extraordinary anthology. In its pages, one finds “a diverse band of colorful characters, wild adventures, and stinging, memorable ‘one-liners.’” Its publication marked an important milestone in the literature of late antiquity. As Peter Brown has noted, “The Sayings provided a remarkable new literary genre, close to the world of parable …

The Apophthegmata Patrum is an extraordinary anthology. In its pages, one finds “a diverse band of colorful characters, wild adventures, and stinging, memorable ‘one-liners.’” Its publication marked an important milestone in the literature of late antiquity. As Peter Brown has noted, “The Sayings provided a remarkable new literary genre, close to the world of parable and folk-wisdom in these Sayings, the peasantry of Egypt spoke for the first time to the civilized world.” And Philip Rousseau has remarked, “Each entry in this fascinating series captures the attention of the reader like a flash of a signaling lamp, brief, arresting, and intense.”

The Apophthegmata was sometimes known by other titles, such as Gerontikon (Book of the Old Men) or Paterikon (Book of the Fathers). The sixth century Palestinian monks Barsanuphius and John of Gaza, as well as their disciple Dorotheos, used these terms. Another common title, the Paradise of the Fathers, was used in a seventh century Syriac collection.

The Apophthegmata has come down to us in two basic forms: the Alphabetical Collection and the Systematic Collection. The Alphabetical gathers some 1,000 sayings and brief narratives under the names of 130 prominent monks and arranges these according to the Greek alphabet. Thus Alpha begins with thirty eight sayings from Antony and follows with those from other notables, such as Arsenius, Agathon, Ammonas, and so on; Beta includes Basil of Caesarea and Bessarion; Gamma, Gregory of Nazianzus, Gelasius, and so on. Attached to certain manuscripts of the Alphabetical Collection is an additional set of sayings and stories that had come down to the ancient editors without names. This series, referred to as the Anonymous Collection, had as its original core some 240 sayings, but eventually 400 more came to be attached to this core.

The Systematic Collection contains many of the same sayings and stoTwo young monks visiting an anchorite at St Macarius Monastery Page 2 ries but gathers them under twenty one different headings or themes, such as “discernment,” “unceasing prayer,” “hospitality,” and “humility.” The Greek version contains some 1200 sayings. In the mid sixth century, an early version of this Systematic Collection was translated from Greek into Latin by two Roman clerics, the deacon Pelagius and the subdeacon John, who perhaps became the later Popes Pelagius and John. This version, called the Verba Seniorum (Sayings of the Old Men), was apparently known to Saint Benedict and powerfully influenced the spirituality of medieval monasticism.

In time, vast collections of Apophthegmata appeared not only in Greek and Latin, but also in Syriac, Coptic, Armenian, Georgian, Arabic, Ethiopic, and Old Slavonic. The linguistic complexity of all this can be daunting. But things are made even more difficult if one seeks to answer the sort of questions scholars raise. For example:

• Does a saying ascribed to Antony really go back to the historical Antony?

• Who gathered these sayings together? When? And why?

• What sources, oral or written, did they draw on?

• Has the wording of individual sayings been altered over time? If so, how? And why?

A number of twentieth century scholars, Wilhelm Bousset, Jean Claude Guy, Derwas Chitty, Antoine Guillaumont, and Lucien Regnault, to name a few of the most prominent have carefully sifted through this huge mass of material and tried to trace out the origins, transmission, and assembling of these collections. Many features of their path breaking studies presume a mastery of the texts, languages, and history that lie beyond the scope of this introduction. But I would like to trace a few of their remarkable discoveries in following chapters. For the moment, let me simply note a couple of their conclusions.

Language.

The Apophthegmata, though written first in Greek (about 5th-6th centuries), drew on an oral tradition that was originally Coptic and that stretched back well over 100 years.

Origin.

The Apophthegmata focuses primarily (but not exclusively) on the wisdom of monastic leaders from Lower Egypt, active from the 330s to 460s, especially those from the monastic settlement of Scetis.

Date and Place of Publication.

Although the Apophthegmata preserves memories of Egyptian monasticism and does so with what seems to be remarkable accuracy the final recording of those memories was not done in Egypt, but in Palestine, probably in the late fifth century. It was from the Holy Land, with its traffic in pilgrims to and from the sacred sites, that these stories of the Egyptian monks spread throughout the ancient Christian world.

(From: William Harmless, S.J. Desert Christians: An Introduction to the Literature of Early Monasticism)

Join Us: Sign Up Today!

Tags: